Quilters have long been known as “repurposers” due to their far-famed talent for taking whatever material happens to be at hand and converting it for use in a quilt. A prime example of this penchant is their availing themselves of textile inserts and premiums distributed with tobacco products as a marketing strategy by cigarette and tobacco companies in the early 1900s.

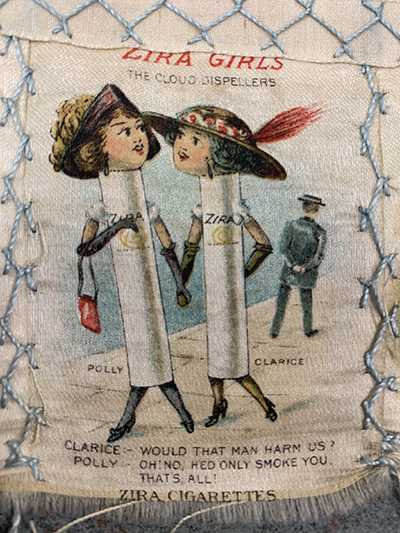

At that time, at least in much of North America, it was not considered “proper” for a woman to smoke. That didn’t stop the tobacco companies from using fabric premiums as a way to endear the sale of their products to women, either as means of approving the purchase by their menfolk or enticing women to smoke themselves.

Photo courtesy of Lisa Erlandson.

The American Tobacco Company was one of the original 12 members of the Dow Jones Stock Index. Within two decades of its founding by James Buchanan Duke (ironically, the major benefactor of Duke University, noted for its medical school), it had absorbed some 250 smaller companies and produced 80% of the cigarettes, plug tobacco, smoking tobacco, and snuff produced in the United States.

Although the products were frequently marketed under the name of the original smaller company, in truth it was the giant American Tobacco Company that owned the business. It so thoroughly dominated the industry that in 1908 the U.S. government brought anti-trust action against it to break up its monopoly and split it into several companies to encourage competition.

Competition, whether real or a façade, is said to have been one of the drivers of the production of novelties or premiums designed to boost sales. Cigars were marketed to a more moneyed clientele, and silk cigar ribbons were popular for inclusion in the Crazy Quilt fad of the day.

Cigarettes were less costly to produce and were considered somewhat lower class; as such they were aimed at buyers with less means and were promoted with a small piece of cheaply-stamped flannel wrapped around ten cigarettes that sold for a nickel, according to Dr. Maggie McGuire, who is writing a book on these tobacco flannels or “felts” as they are sometimes called.

Quilters, doing what quilters always do, saw this “free” fabric as something they could use, and in fact the tobacco companies encouraged the creation of domestic items, including quilts, from the flannels, despite their being notoriously flimsy with totally unstable dyes.

Dr. McGuire says that between 1904 and 1911, thousands of these flannels were produced in a dizzying array of subjects (with no attempt at accuracy) that included flags of the world, military soldiers, Native American blankets, Oriental rugs, butterflies, animal skins, flowers, baseball players, Rosie O’Neill Kewpie dolls, nursery rhymes, college and university flags and seals, athletes, famous people, and so on.

United States flags were among the most popular subjects, and it was possible to accumulate several smaller flannels and exchange them for a larger flag premium. The tobacco flannels were collected and traded and despite their instability, quilters did use them to make “quilts” that were clearly intended for decoration rather than regular use.

World War I ended the large scale production of tobacco flannels because cotton was needed for the war effort. For a brief period, however, these cheaply-made, brightly-colored novelty items made their own contribution to the remarkable richness of quilts.