Do you ever wonder, as I do, how certain quilting terminology came into being? Like any subculture, the quilt world has its own jargon. Some of the terms we use or the special definitions we give to certain words can be confusing or even unintelligible to the uninitiated. Layer cakes and jelly rolls have different meanings to quilters than to bakers, for example. To a quilter, bearding has nothing to do with facial hair, bleeding is not about blood, loft is not the attic, feed dogs do not refer to pets needing dinner. And so on…

One term that has always piqued my curiosity is the Baptist Fan. The fan has long been one of the most common utilitarian quilting designs, at least in the southern United States. Maybe it was quicker or a tad fancier than just plain quilting “in the ditch” (quilting in or near the seams that join the pattern pieces). But in any case, it was certainly one of the go-to designs for the quilters I grew up around in rural Texas.

My Aunt Neva quilted her quilts in a large frame, almost always with friends. When doing the fan design, she would not mark the top before it went into the frame, but rather she used a sort of mark-as-you go arrangement after the top and batting were already pinned or basted to the backing in the frame.

She would take a piece of string that had been knotted at regular intervals. Then she’d hold the string at the first knot at the middle of where she wanted the design to start, insert a pencil (or a piece of chalk) into the next knot, and draw an arc. She’d then move the pencil to the subsequent knot (still holding her finger tight on the first knot) and make a second arc. This went on until for as many arcs as she wanted to complete the fan design.

Basically, it was a homemade version of a Swing-Arm Compass. I’m not sure if that’s what other people did but it worked for her. If she was quilting with friends, the string and pencil apparatus was passed to the next person sitting at the frame, who would draw the fan arcs on the section of the quilt in front of where they were sitting. When the quilt was rolled, a fresh set of arcs would be drawn, with the base point being in the dip between the first set of arcs.

Since the design was marked and quilted from the quilt’s edges inward, it was difficult to make the arcs meet in the middle. Most older quilts with the fan design have a thin strip down the center marking this discontinuity. Old-time Texas quilters called this strip “the hog’s back,” probably because it is reminiscent of the ridge along the back of a big pig.

Because Aunt Neva was making utility quilts for everyday use, she would sometimes forego the string and pencil altogether and just eyeball the arcs, which made for some wonky rainbow-shapes that nevertheless got the job done. The concentric arcs were easy to quilt because the needle could always move in the same direction and the quilter didn’t have to twist her arm around to follow the design—the arcs follow the natural movement of the arm.

So how did “Baptist” get attached to the fan name? Aunt Neva was a staunch member of the Church of Christ, but she still called that design the Baptist Fan (she also sometimes called it a shell, but perhaps that was because she didn’t want to give too much credit to the Baptists).

I’ve read that in other places, it was called the Methodist Fan or even the Presbyterian or Lutheran Fan, which seems to anchor it to members of a certain church group who quilted together, maybe for church-related fundraisers. Perhaps the moniker varied, depending on the dominant religious denomination in any given area. Thinking back on it, there really were a lot of Baptist churches where I grew up.

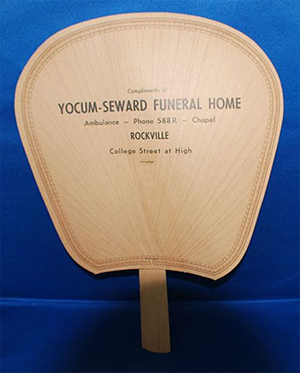

Another theory posits that the shape mimicks the paper fans that were given out at churches to keep people cool during a long, hot sermon before the days of air-conditioning. The Southern Quarterly, a publication of the University of Southern Mississippi, says this: “Church fans used to be among the most prominent items in Southern religious culture. In the early twentieth century, printers began producing inexpensive cardboard fans on wood handles for businesses to purchase and distribute with information on the back. Funeral homes and insurance companies—businesses dealing with death—most typically used the fans to get their message out to congregants hoping for the rewards of an afterlife that would surely be cooler than hot Southern Sunday mornings.”

Who really knows how the Baptist Fan quilting design got its name? I’m guessing that its true origin would be impossible to verify. To me, though, the term is just one more colorful aspect that adds to the rich topic of quilts.