Certain novelty techniques (such as yo-yos or the Cathedral Window) involve folding and stitching small pieces of fabric in various ways to produce three-dimensional works that are not really quilts in the traditional sense of a top, batting, and backing all stitched together.

Nevertheless, these thrifty, scrap-using methods have been so wholeheartedly adopted by quilters for such a long time that a special niche has been carved out for them in the quilt world, and they are referred to as quilts even though they don’t strictly fit the description. Another honored member of this particular group is the Pine Burr.

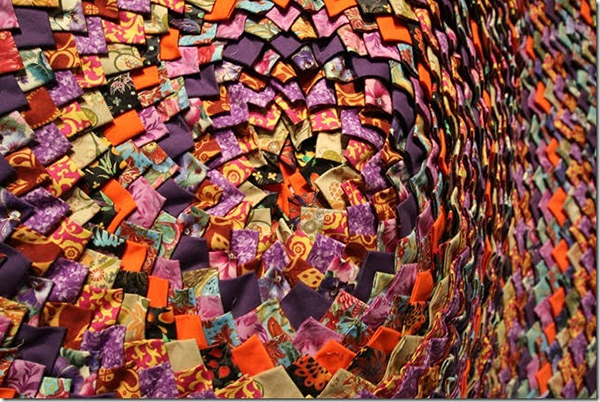

The Pine Burr is constructed of folded triangles (prairie points) sewn side-by-side onto a foundation in concentric circles. The resulting design resembles a target, and that is an alternate name for this type of quilt, which is also goes by many other names, including Pine Cone, Cocklebur, Arkansas Burr, Lumbee Pinecone (after the Lumbee Native American tribe in North Carolina who use the design in many of their traditional crafts), and a variation, Somerset Star, in the United Kingdom. Bed-sized Pine Burr quilts require so much fabric that they end up being quite heavy, weighing over 25 pounds depending on the size of the finished piece and the type of fabrics used in it.

Many quilt patterns change names depending on who is making the quilt and where it is being made, and a particular pattern can become associated with a particular group. Such is the case with the Pine Burr. According to quilt historian Cuesta Benberry, “From early to late twentieth century, the Pine Cone quilt was popular among southern African-American quilters.” In 1997, the Alabama State Legislature named the Pine Burr its official state quilt, the only state to have such a designation. In truth the Alabama Legislature was honoring the women traditionally associated with making Pine Burr quilts in that state as much as the pattern itself. The official proclamation states, in part:

WHEREAS, the Freedom Quilting Bee was organized as an outgrowth of the Civil Rights Movement in 1966, one of the few all Black women’s cooperatives in the country; and

WHEREAS, the Freedom Quilting Bee has achieved national recognition for its quilts by using designs that come from a 140-year-old tradition; and

WHEREAS, China Grove Myles, a farmer, was the only one left in Gee’s Bend who could sew the Pine Burr Quilt, a pattern involving hundreds of tedious swatches that unfold before the eye in a breathtaking, three-dimensional effect; and

WHEREAS, Nettie Young, also a farmer, is the only woman now working at the Bee who was among its originators, and who typifies the history of the Black race in Alabama;

It was a Gee’s Bend quilter, Loretta Pettway Bennet, who made and donated the official Pine Burr quilt to the Alabama Department of Archives and History in 2005. She was taught how to make the quilt by her mother Qunnie Pettway, a member of the Freedom Quilting Bee.

Betty Ford-Smith, an educator turned quilter, has made it her mission to keep the tradition of the Pine Burr (or Pine Cone as she prefers to call it) quilt alive. Betty learned to make the pattern from a remarkable 92-year old African-American woman known as Miss Sue (her real name was Arlene Dennis) who was making and selling the quilts from her home in Sebring, Florida.

Betty began an apprenticeship with Miss Sue in 2004 that continued until Miss Sue passed away in 2010. “I completed two quilts with her supervision,” recalls Betty. “She, however, completed four while I was with her.” Miss Sue led an extraordinary life (including outliving all but one of her 12 children and killing a man in self-defense after he stabbed her in the head), which Betty documented in a book she has written entitled Miss Sue and the Pine Cone Quilt.

Betty credits Miss Sue and learning how to make this particular quilt pattern with helping her through a particularly difficult period in her life and in fact Pine Cone quilts now define her professionally. She has taught the pattern to hundreds of women in the United States and France, and she has exhibited her own Pine Cone quilts widely to much acclaim. She spends as much as ten hours a day making them. To date, Betty has completed 12 full-sized Pine Cone quilts, all by hand, working with the pieces in her lap (a time-consuming—and certainly weighty–endeavor) the way Miss Sue taught her.

The Alabama Department of Archives and History offers step-by-step instructions for making a Pine Burr Quilt. To see them, click here.

(All photos courtesy of Betty Ford-Smith.)