Appliqué is a decorative textile technique that has been employed by cultures all over the world since ancient times. While tracing the exact origins of appliqué may be impossible, an example of a ceremonial funeral canopy featuring appliqué work dating to 980 BC is among the holdings of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Certainly, human beings have been sewing one piece of fabric over another for a decorative effect for a very long time.

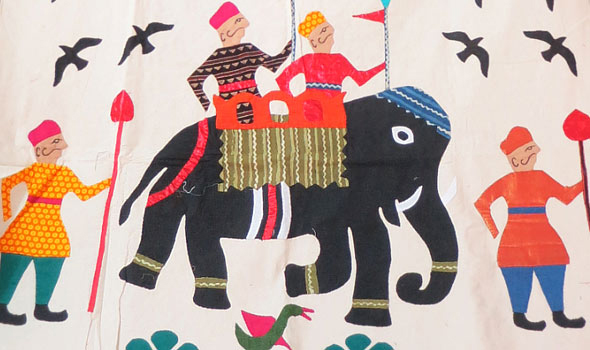

One of the places where appliqué has an age-old history is India, and in particular, the western coastal state of Gujarat. Gujarat has for centuries been a center of textile production and even today it is known as “the textile state of India,” producing everything from silks and cottons to polyesters. A rich cultural heritage and generations of craftspeople traditionally involved in fabrics contribute to Gujarat having a major contributing role in India’s dominance of the global textile market.

One of the world’s most extensive textile museums is in Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city. The Calico Museum of Textiles was founded in 1949 as part of Calico Mills, which was among India’s oldest cotton textile mills. Although the mill closed in 1998, the Museum remains and contains an extraordinary collection of Indian textiles dating to the 15th century. Prominent among these are appliquéd items made by a variety of native Indian communities. These communities in Gujarat still produce appliquéd items to the extent that it is considered one of the major handicrafts identified with the state.

One such native community is the Rubari, a population of semi-nomadic camel herders. Although many Rubari have integrated into modern society, the women of this community are still recognized for their needle skills, especially appliqué (known as katab), which is often combined with patchwork, embroidery, beadwork, and mirror-work. Traditionally and still today, the women have made dowry items, quilts, tent canopies, animal covers, door hangings, and the like by recycling waste fabrics from local tailors and garment manufacturers.

Necessity has forced many Rubari women to sew for commercial clients in order to make a subsistence living for their families without any creative control over what they produce. In 2014, two textile artists/researchers, LOkesh Ghai and Emma Sumner, established a project they called “Katab: Not Only Money” in order to establish a sustainable model on which the Rubari women could make and sell their quilts directly without agents and thus allow them to earn a better income with artistic control. The 2019 British Textile Biennial featured a group of these quilts that were inspired by Bollywood films and Hindi TV series.

Through efforts such as “Katab: Not Only Money,” the skill of appliqué among Gujarati’s indigenous populations will remain a vital component of a long and rich cultural tradition in India.