The Lumbee Native American Tribe is concentrated primarily in four southwestern counties in the state of North Carolina along the South Carolina border. The Lumbee derive their name from the Lumber River, which flows through that area. They are the largest Indian tribe in North Carolina, the largest tribe east of the Mississippi River, and the ninth largest (some 60,000-strong) in the United States.

The part of North Carolina where the Lumbee are concentrated is also home to a concentration of Longleaf pine trees. Longleaf pines are a conifer native to the U.S., distinguished by their namesake 6- to 18-inch drooping needles and large (up to 12 inches long) pinecones that hang down from the branches. At the round base of the cone, the seeds are tightly packed in a spiral design that has inspired generations of Lumbee artisans in basketry, woodworking, jewelry, rugmaking, clothing, and—as it turns out—in one particularly important quilt.

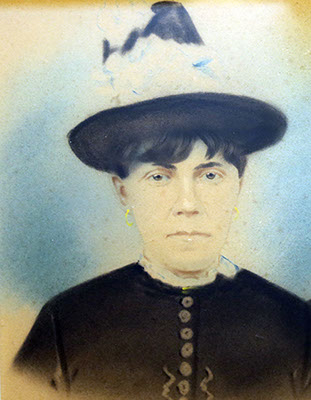

In the late-1800s, Maggie Lowry Locklear, the daughter of Henry Berry Lowry (a Lumbee well-known during the Civil War as a Robin Hood figure and an early activist for tribal self-determination), made a quilt inspired by the Longleaf pinecone. Using scraps of pants fabric (from three husbands) and other clothing, and she created 15 blocks of tiny folded triangles sewn onto a foundation in concentric circles and striped together into a full-sized quilt.

While the technique strongly resembles the Pine Burr pattern, Maggie’s method was slightly different in that her pieces were not prairie points (i.e., a square folded to make a finished triangle with an open edge on the side and ironed down flat). Instead, Maggie’s triangles appear to have been folded an extra time before being sewn down, giving them an even more dimensional effect, rather like the point of a crayon. Each of the blocks contains over 2,000 pieces of fabric.

The quilt gained fame even during Maggie’s lifetime, and many tried to buy it, but Maggie always refused to sell. Today Maggie’s quilt resides in the Museum of the Southeast American Indian on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. It is a public, historically American Indian liberal arts university with deep ties to the Lumbee nation.

It was there that the quilt inspired an artist named Hayes A. Locklear (likely a distant relation of Maggie’s last husband). In 1993, Hayes Locklear used his interpretation of the quilt in such a way that has given the pinecone patchwork pattern renewed significance for Lumbee tribal members.

He created what he called a “Lumbee dress” that featured a recreation of Maggie’s pinecone patchwork pattern.

According to Alisha Locklear (“We’re all related somehow”) Monroe, the director of education at the Museum of the Southeast American Indian, “That first dress was made of humble fabrics and reflected the Lumbee traditional dress, including an apron and a matching shawl, but he decorated the apron and the shawl with the pinecone patchwork pattern like on Maggie’s quilt. When Natasha Wagner, who had won the Miss Lumbee pageant, saw the dress, she asked Hayes Locklear to design a dress for her to wear in the Miss Indian World competition that would reflect the history and culture of the Lumbee people. She went on to win the title of Miss Indian World in 1993, and since then the Lumbee pageant has adopted the pinecone patchwork dress as its official costume. Today the dresses are a lot glitzier with fancy fabrics and beads, but they still always have the pinecone patchwork and show the pride that we have in our traditions.”

The pinecone patchwork pattern inspired by Maggie’s quilt has led to a revitalization of artistic traditions among the Lumbee. In addition to dresses being worn for parades, pow wows, festivals, and other important socio-cultural ceremonies and events, artists are fashioning other types of art that feature the pinecone patchwork design. The Museum holds quilting classes at which the pinecone patchwork design is taught, and the pattern is taught at community quilting bees throughout the Lumbee tribal area. “Maggie’s quilt has become a really important symbol of Lumbee heritage,” continues Alisha.

According to Maggie’s daughter, Emma Lee Locklear, the quilt was her mother’s conscious effort to make something in a traditional tribal design that would be recognized as a symbol for the Lumbee people. Although Maggie could hardly have foreseen the legacy that her quilt has inspired, she doubtless would have approved.

All photos courtesy of the Museum of the Southeast American Indian.