When something is said to have been reclaimed or reappropriated, it means that a group has brought back an idea, custom, or object that had once been used by others in a way the group perceived as negative or hurtful. An example of this is the term queer, which was once considered a slur but has now been reclaimed with a positive meaning by members of the LGBT community.

For Susan Hudson, a member of the Kin Yaa aanii (Towering House People) Clan of the Navajo Nation who lives on the Sheep Springs on the Navajo Reservation in New Mexico, the thing she has reclaimed is not a verbal slur, however. The thing she has reclaimed is quilting.

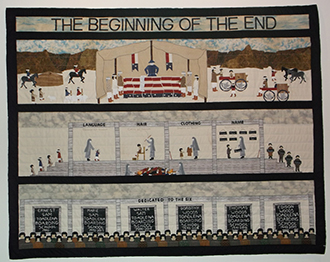

For more than 100 years following the Civil War, many Native American children were forcibly removed from their families and taken to attend remote Indian boarding schools, run by the government or religious organizations. The focus of these compulsory schools was the assimilation of the children into Anglo-European culture.

Students were given a basic academic education, but were forced to give up their indigenous identities and cultures. They were severely punished if caught speaking their native languages. Their Indian names were replaced with Anglo names and they were given American haircuts and required to wear uniforms or American clothes. Physical, mental, and even sexual abuse were not uncommon in the schools.

Things began to change only in 1976, after the U.S. Congress passed the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act and by 1990, when Congress enacted a law to protect Native languages, tribal involvement in education had become the norm. Most boarding schools were closed.

Both Susan’s grandmother and mother had been forced to attend Indian boarding schools and one of the things they were made to do was make quilts. They were beaten if their stitches were not small enough or if they made mistakes. “I asked my grandmother if they got to use the quilts they made on their beds to keep warm and she said no,” says Susan. “She told me the school would sell the quilts, but the girls never saw any of the money. So basically, it was child labor.”

Susan comes from a long line of Navajo artists, including Master Weaver Mary Ann Foster, Master Weaver Hastiin Klah (who inspired the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, New Mexico), and many well-known jewelry makers.

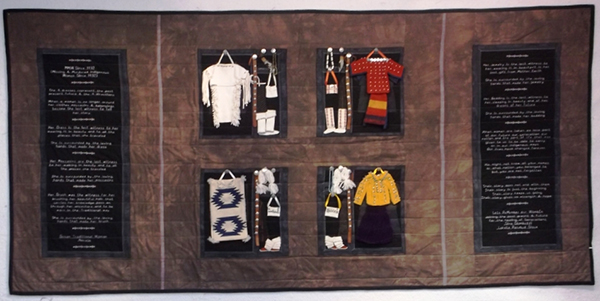

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Since 1492 by Susan Hudson, 2017. Currently on exhibit at the Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe, NM.

“Even though I have all these artists in my family background, I can’t weave, paint or make jewelry, but my mother, Dorothy Woods, taught me to sew when I was nine-years-old, and she also taught me how to quilt,” Susan explains. “I decided that making quilts was going to be how I would honor her and all the Navajo mothers who were forced to give up so much and forced to do things like quilt. I would turn something negative into something positive.”

Walk of My Ancestors: Coming Home, by Susan Hudson, 2016. Purchased by private collector and donated to the Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles, CA.

Susan has certainly accomplished what she set out to do. Her remarkable pictorial quilts Have won many prizes and are held in the collections of major museums, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, and the Heard Museum in Phoenix. Her work was recently featured at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe.

Although she began making utility quilts as a child with her mother and grandmother, Susan parlayed that knowledge into an income stream when she began making Star Quilts for Indian pow wows and giveaways at the request of Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a former U.S Senator from Colorado. Senator Campbell recognized Susan’s innate talent and encouraged her to break away from making traditional star quilts and find her own artistic voice.

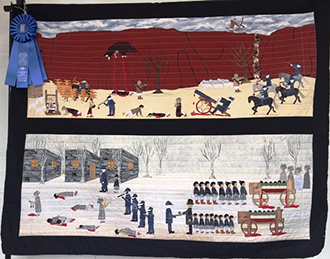

Susan had long admired the ledger art of Plains Indians. (Ledger art is a type of narrative drawing or painting traditionally done on animal hides. It evolved to be done on ledger books and other paper obtained from military officers, government agents, traders and missionaries and flourished when Plains tribes were forced to live on reservations in the late 1800s.) “Indians have an oral tradition, not a written one,” Susan explains. “We tell our stories in pictures. But instead of using paper, I use fabric.”

She began to make what she calls ledger quilts, which depict stories from her heritage in fabric, and she has become renowned as the Contemporary Ledger Quilter. Her process begins with prayers and dreams.

“In my dreams I’ll see images of my ancestors and all the horrible things they had to endure. I think about them being forced to leave their homelands and go to reservations and the children being made to go to the boarding schools. I think about the Long Walk of the Navajo. The pictures stay in my mind and I’ll pray about them. Pretty soon it comes down to just a few and I’ll go to my place on the mesa to decide what I want to do. I know if I start crying about an image, I’m going to make a quilt of that,” she continues. “If I have trouble with the design, I ask my spirit helpers to help me. Sometimes I hear my grandmothers talking to me. It can take me as much as 18 months to make a quilt.”

Above: Walk of My Ancestors: Coming Home, by Susan Hudson, 2018.

The depth of feeling that Susan puts into her work is evident in the quilts she makes. By evolving a traditional means of expression into a different medium, she is proving once again that quilts provide a perfect vehicle for telling a story.