Note: This continuing series reposts some of the most memorable columns of Suzy’s Fancy, which ran from 2009-2020. This piece originally ran in November 2014.

Most quilt lovers with even a passing knowledge of fabrics can identify a quilt made in the United States during the 1930s. The iconic pastel color palette is a hallmark of Depression-era quilts and a reliable indicator of the time period.

But what is perhaps less widely recognized is how those characteristic colors came into existence at that particular time. It’s an interesting story with surprising cloak-and-dagger elements, tales of spies, kidnapped chemists, and stolen secret dye patents.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Germany pioneered industrial research that led to that country’s dominance over the world’s production of synthetic organic chemicals, including dyestuffs.

In rare cases, German chemical firms like BASF and Bayer would set up manufacturing plants in other countries (Bayer had a factory in Albany, New York, for example), but mostly their products were distributed as exports, and all the dye formulas and technical know-how remained in Germany.

When the so-called “Great War” began in 1914, Germany was producing 90% of the dyestuffs used in the manufacture of fabrics throughout the world.

Throughout the war, from 1914 to 1919, the Allied countries staged a naval blockade of Germany. While this operation restricted the maritime supply of raw materials and food from getting into Germany, the action, of course, also kept German goods from getting out.

The inability to get German dyes led to what became known as “dye starvation” or “dye famine” in America.

According to Robert J. Baptista, writing for the Colorants History website, “The demand for domestic dyes was insatiable during the war and selling prices rose spectacularly. In 1914, sulfur black, one of the largest volume dyes used in the textile industry, sold for $0.20 per pound. During 1915, the price soared to $2.75-3.00 per pound. Dye-making suddenly became one of the most profitable industries in the U.S., attracting investment by both small and large firms. However, there were few American chemists with the requisite know-how of dye-making and this presented a major technology barrier.”

Some accounts even refer to World War I as “the chemist’s war,” because of the newfound realization of the importance of industrial research and production of synthetic chemicals.

At the end of the war, Germany was forced to surrender its patents, including those for dyes. When that happened, one American dye authority at the time declared: “[The surrender] includes the production know-how and the secret formulas for over fifty thousand dyes. Many of them are faster and better than ours. Many are colors we were never able to make. The American dye industry will be advanced at least ten years.”

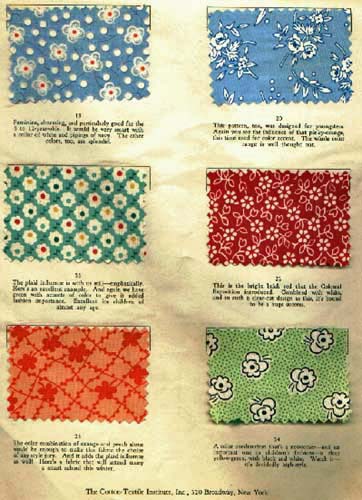

And so it was. Germany’s synthetic dye patents allowed American dye manufacturers to produce, for the first time, colorfast shades of pink, blue, yellow, green, aqua, peach, and lavender. The textile industry in turn began to produce cotton fabrics featuring flowers, geometrics, and playful conversational prints in the now-available rainbow of pastel colors. And we all know what quilters did with those!